Did I mention that writing is hard work? And that when it comes to the hardest parts, novelists have this damnable tendency to tell themselves they're lousy writers, when in fact what they've got ahead of them is just plain hard work. The damnable tendency is a subject I'll deal with another time. Today it's about one of the hard jobs of writing. That elusive and confusing thing called Pacing. It's a Dragon. Let's slay it.

Anyone who thinks he can just sit down and write the fantasy of his heart and call it a novel- well, maybe he can write it. But if he thinks it's readable, he's probably wrong. Because 90% of the work in producing a novel others would want to read is in the re-writes. And most authors don't know how to edit for better pacing.

So let's gather our weapons and do a little reconnaissance.

Pacing is hard even to define. Basically, good pacing is the combination of all parts of a story to make it flow in a way that enhances the story. It' a matter of timing. Just as a comedian knows he must time his joke perfectly or it will fall flat, so an author must time his story.

As authors we can work magic with time. We can alter it as we please, and our readers accept it- if we did it in a way that serves our story well. The rest of the world is stuck with this ever-ticking clock that advances forward at the same eternal pace (other than the ones Einstein decided to move at the speed of light, that bring their travelers back to earth still young when everyone they knew on earth has aged and gone to their graves, but we're not going there today.)

Think about it. You pick up my book and spend a few hours reading it. In that amount of reading time, I took you back in time and we journeyed several months together. We might have skipped forward- I tend to discount hours spent sleeping as boring parts not worth recording, and hop right past little trips to the outhouse unless they're significant). We might have back-flashed to a previous ti

me.

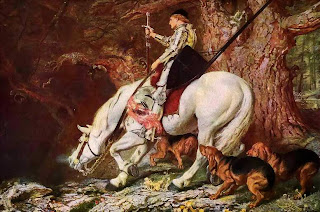

me.But that's only the obvious part. We also might have slowed time to luxuriate in a place of utter pleasure, say, floating down a very lazy river with the sun dappling through the trees along the shore. Or we sped it up to leap on our horses and dash over the fields to the churchyard where the bad guys hold the heroine hostage. And all in all, our story held us in the magic thrall of time, the illusion that we'd lived all of that, plus the memories of the events that led up to the story.

It's magic. Because it all happens by words. I say "horse", and you picture horse, complete with flowing mane. But no horse is really there, just in your mind and mine. I take maybe 2 seconds to say, "next morning", and your mind jumps to there, accepting that eight hours have passed. If I documented all those eight hours, you wouldn't just throw my book against a wall, you'd hunt me down and beat me to death with it.

Yeah, you say, but WHAT WORDS? Yes, that's the trick. Well, actually, the trick is more in HOW MANY words, and WHAT Kind of words.

In other blogs I've talked about cutting out the boring stuff and starting at the right place. Those are important parts of good pacing. The first thing is the boring stuff. What's boring? Anything that isn't really part of the story, and story is about conflict and conflict resolution. So idle conversation is a story killer because the reader has to dis-engage from the story and listen to chatter that in another situation might interest him but does not now.

The same is true with extra words. This has been a really hard one for me to learn. Women are more verbose than men, and they use more 'qualifier' words, like 'maybe', 'I think', 'rather', 'part of me thinks'-- get the idea? They have their uses, but they slow things down. So whenever you want your story to move faster, go on a hunt for qualifiers and slay them as mini-dragons. So just as a matter of habit, get rid of them through your entire story.

Slow scenes are hard to master, but I find most contest entries and even some published books have a really hard time with action scenes, where the pacing must be very tight and tense. For some reason it's common for authors to over-write action scenes. Sometimes I think they believe they have to get in more information to be believable. But actually, this is the time to t

rim to a bare minimum. The first thing that needs to go is internal monologue because the last thing a person is doing when he sees a car screaming down on him is to think, "I wonder if that's my Cousin Dewey. He always hated me after his dad took me on that fishing trip to Yosemite Park. I remember Aunt Maud wearing the dress with the tiny flowers as she packed our balogna sandwiches in brown paper bags..."

rim to a bare minimum. The first thing that needs to go is internal monologue because the last thing a person is doing when he sees a car screaming down on him is to think, "I wonder if that's my Cousin Dewey. He always hated me after his dad took me on that fishing trip to Yosemite Park. I remember Aunt Maud wearing the dress with the tiny flowers as she packed our balogna sandwiches in brown paper bags..."No, he's going to get the h&!! out of there, and think about Cousin Dewey and mouth-watering balogna later. So f it's possible, get rid of every single bit of internal stuff.

Also tighten with short, hard-hitting words. Short sentences.

Go on a modifier hunt, and slay that mini-dragon, too. If it ends in -ly or -ing, chances are excellent it needs to go. Look for verbs that do double duty. Verbs that require a modifier are generally weak ones, and you'll get more impact plus faster pace if you find a verb than can say what both verb and adverb are saying now. Limit the number of objects you describe. If you have a string of visual things you put in your description, pick ONE, describe it quickly (one word or less) and get on with the action.

Look closely at your nouns, too. Don't say feline when you can say cat. Better yet, get specific and say Persian. Yes, the word is longer, but it gives a more vivid picture, and you need all the help you can get with visuals here. Also be sure you've varied your words because a slightly different word can contribute more information just by being there.

Pronouns? Use them but be sure they refer to the right person, place or thing. Nothing worse than confusing the reader to slow down pacing.

And emotion- substitute it for all that thinking you took out. Also body language, and PAIN. If your hero takes a bang on the head, he'd better feel it or you lost your reader, who won't take it seriously.

And in an action scene more than any other, do not say anything twice, just in a different way. Don't follow a great piece of action with a short internal thought about what or why. Show it all in the action.

But there's one dragon that above all must be slain: Lack of Conflict. Your fiction must be conflct from beginning to end, even in the slow, easy scenes. Every scene must have a problem, and something must happen to change the scene so that when it is done, the characters' world and situation has changed. If not, then you need to find out what the conflict is that you've left out, and if you can't find it, then your scene needs to be cut.

I've read several contes

t entries lately in which the author has worked very hard to beef up the pacing. The prose is so tight, if it were a trampoline it could bounce you to the stars. But somehow it still falls flat.

t entries lately in which the author has worked very hard to beef up the pacing. The prose is so tight, if it were a trampoline it could bounce you to the stars. But somehow it still falls flat.Why? No amount of tightening can take the place of good work on Goal, Motivation and Conflict. If you have characters that are walking around town talking about yesterday's ballgame, I have a hard time caring. I can hear that at home. If they walk out of the game arguing over whether the game was thrown, sorry I still don't care, because that's just arguing and it's not going anywhere. It isn't true conflict as far as fiction goes. But if a car screams up, masked men jump out and grab a guy's girlfriend and drag her off, gunning down the boyfriend in the process, then I want to know why. A story has begun.

Whew! Did I mention this Dragon-Slaying is hard work?

No comments:

Post a Comment

This is a discussion blog. Spam of all kinds, including unrelated book promotion, is not welcome and will be diligently removed.